Department of Energy Pushes Elios 3 to Its Limits to 3D Map an Old Vault Made to Store Radioactive Waste

BY Zacc Dukowitz

20 December 2022In the middle of nowhere in Idaho, in a top secret facility called the Idaho Nuclear Technology and Engineering Center, lies an underground vault that stores over 720 cubic feet of radioactive waste.

The vault is behind high barbed wire fences, guarded by men with guns. It was built in the 1950s and contains four giant stainless-steel bins, each one 20-feet tall. Each of these bins holds calcine, a highly radioactive, granular solid made from spent nuclear fuel.

Back in 2015, the state of Idaho told the Department of Energy (DOE) that it didn’t want to store this radioactive waste any more.

The problem?

The vault and bins were made for permanent storage. No plan exists for removing the calcine, or even for what exactly the interior of the vault looks like.

What’s In the Vault?

To make a plan for moving the radioactive calcine, the DOE contracted with an organization called the Idaho Environmental Coalition (IEC) to figure out 1) how to remove it, and 2) where it should go.

After extensive research, the IEC came up with a solution. By drilling hole into the vault then robotically cutting a hole into the top of each bin, pipes could be attached to the bins that could pneumatically suck out the calcine.

There was just one problem. There were no detailed blueprints of the vault, so there was no way to know if there was a clear path for the pipes to be lowered into the vault.

To better understand the interior of the vault, the IEC needed to create a 3D model of it. Due to the high levels of radiation in the vault a person couldn’t enter it, so everything done inside had to be done remotely—either using robotic solutions or using tools, like handheld LiDAR sensors, lowered down by ropes.

3D Modeling by Drone in Confined Spaces

This is where drones enter the story—specifically Flyability’s Elios 3 indoor drone.

In the end, the IEC chose the Elios 3 as the ideal solution for creating a 3D map of the vault’s interior to help with planning for removing the nuclear waste stored there.

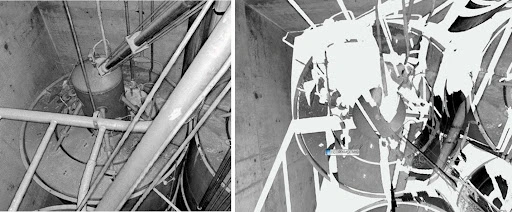

Before landing on the Elios 3 as the best solution for 3D mapping the vault, the IEC first tried lowering a handheld LiDAR sensor into the area using a rope so it could create a 3D map. But the sensor couldn’t collect all the data needed, and the resulting 3D model had gaps (see below).

To find the best solution, the IEC systematically investigated different methods for collecting the data.

In total, they looked at five different solutions, including the use of an articulating arm, a helium-filled blimp, and drilling holes into the vault.

After exhaustive research, the IEC team decided that the best option was to use an indoor drone from Flyability. At the time, the Elios 3 hadn’t yet launched, so the plan was to use the Elios 2 to collect visual data and then process that data with photogrammetry to create the 3D model of the vault’s interior.

[Learn more about the IEC’s selection process for finding a 3D mapping tool.]

After selecting the Elios 2, the IEC later learned about the upcoming launch of the Elios 3 and decided to use it instead. The Elios 3 is equipped with a LiDAR sensor, which allows it to create more accurate, detailed 3D models than photogrammetry can make.

The Elios 3’s LiDAR data allows it to make 3D models in real time, as it flies, as well as allowing users to make 3D models in post-processing after the flight with software from GeoSLAM.

To prepare for the data collection mission, the IEC built a life-sized replica of the vault in a warehouse. Eric English, Drone Operations Manager at Flyability, conducted intensive training exercises with IEC pilots to get them ready.

Watch this video for an overview of the training that went into preparing for the vault mapping mission:

Flying Inside the Radioactive Vault

After months of planning and preparation, the day of the mission arrived.

A large plastic tent was placed over the entire top of the vault, meant to make the mission technically take place indoors according to FAA regulations and DOE requirements. In total, about 50 people helped with the mission, providing support by opening the vault using a crane and preparing it for the flight.

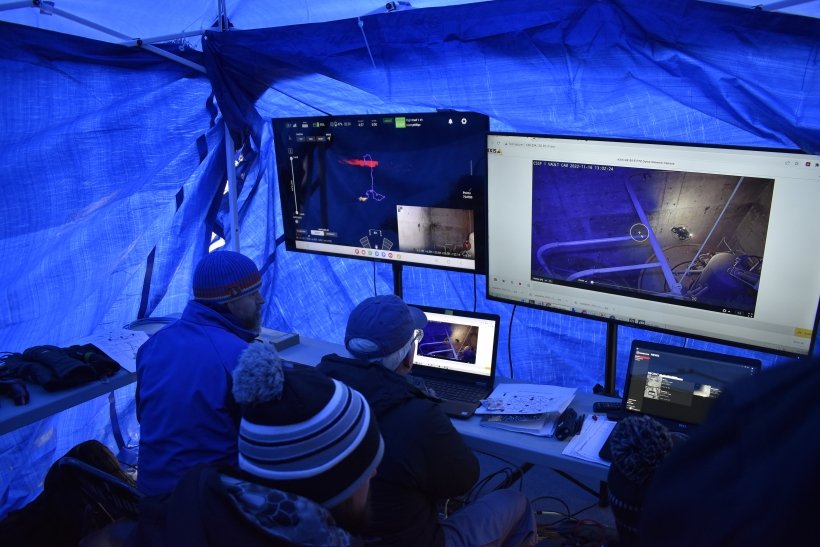

The operations control center on the day of the mission

Finally, it was time to fly.

It was quite cold and windy that day (about 12° Fahrenheit) and the pilot flying the mission knew that it would be hot inside the vault (well over 100°), presenting large fluctuations in temperature that could impact the drone’s performance.

With everyone on pins and needles, the pilot armed the Elios 3 and flew it into the hatch. Kevin Young, the project manager for the operation, looked on nervously as the drone’s 3D Live Map and live visual feed projected onto large screens (shown above), watching as the drone flew through the vault, collecting LiDAR and visual data the entire time.

The first flight took only seven minutes—the Elios 3’s battery life is about 10 minutes but the pilot didn’t want to risk flying for longer given the uncertainty of how the temperature extremes might impact the drone’s performance.

In that seven minutes, the IEC team was able to collect all the data it needed to map the interior of the vault.

To put this another way, a single seven minute flight was the end result of months of exhaustive research, planning, and preparation. To be sure they had enough data, the team tried a second flight, resulting in even more data that could be used to map the vault’s interior.

Now that the vault has been mapped, the IEC faces the next difficult task—actually removing the radioactive waste.

No plans have been announced yet for when this will happen, but it seems likely it will take place some time next year.

Ultimately the IEC will have to remove nuclear waste from six different vaults, for a total of 14,436 cubic feet of nuclear waste. Once the first vault has been emptied, the remaining five will go more quickly—that’s the hope, anyway.